“Das hört nicht auf. Nie hört das auf”

Günter Grass. «Im Krebsgang»

“It doesn’t end. Never will it end”

Günter Grass. «Crabwalk»

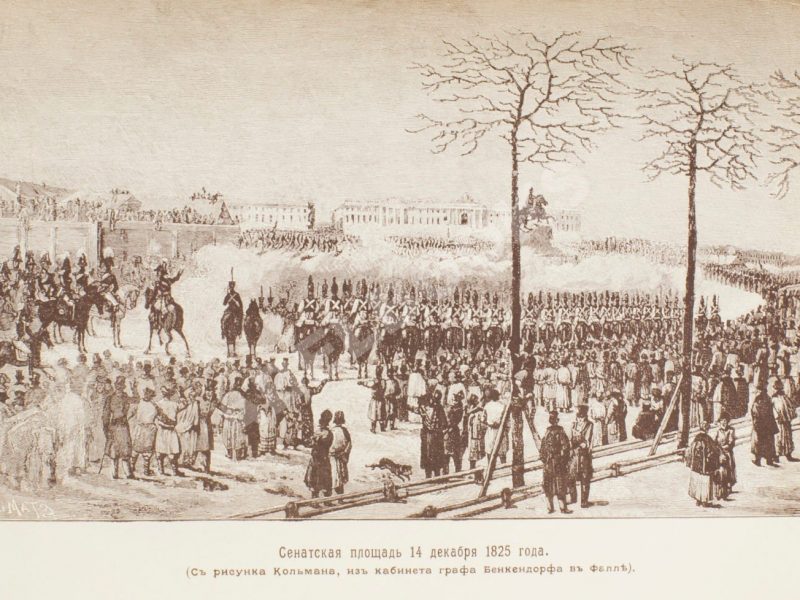

August 5 is the day of remembrance for victims of the Sandarmoh massacre, one of the largest and most bloody shootings of the Soviet special services.

For me, this is a place of memory and this day is special. My grandfather lies out there somewhere among almost 7 thousand decayed skeletons. He was shot in the back of the head with a revolver in one of the shooting pits on November 4, 1937.

I do not want to write about this tragedy, which I have already addressed more than once. Rather, I would like to think about what is historical memory in general? Is it needed? And if so, why? And is it possible to equate history as a science, that is, impartial knowledge of the past – and memory, namely, a morally coloured social myth? And can history be considered a science at all if it cannot prove anything by observation or experiment? Or is history as a science just a “camouflaged memory,” a morally coloured myth, and not an impartial knowledge at all?

I want to start with the term ‘history.’ I believe that ‘history,’ although not an exact science (and therefore not completely a science), ideally seeks to be a science. And so it should be separated from “social mythology.”

Historians narrate according to the rules of academic discourse and do not rally agitation. They argue reasonably, they do not conjure. They answer the questions: “What?” And “Why?”. That is, they establish causal relationships, and do not place moral emphases, do not explain what was “good” in the past and what was “bad.”

History as a science does not know good and evil, but only cause and effect. It is equally interested in sacrifice, the executioner, war, peace, genius, and villainy. Historians are obliged to at least pretend that they are striving for this, even if internally they are not free from personal memorial predilections.

Memory, on the contrary, exists only in order to place moral emphases.

History strives for scientific truth, although it cannot achieve it. Memory strives for moral truth, however, it never fully obtains this truth, for the falsity of the myth is always “treacherously peeking out” from behind one or another magnificent monument.

But can memory be actual and correct at all? Yes. “Correct memory” is a memory that selects from the past what it needs, but does not falsify the facts. At the same time, the “right” memorial myth can be both constructive and destructive – if it pushes society into a whirlpool of aggression under the guise of consolidation. “Wrong memory” is completely false. And such a myth is always socially destructive, for it destroys society from within, and by no means consolidates it.

Memory is the basis of self-consciousness for any society. Society simply cannot be formed and exist, without the myth of its roots sprouting from the past to the present.

In the vast majority of cases, the memory of society is the memory of the victims. And therefore, the German philologist and memorist Aleida Assmann proposed dividing the memory into two “sacrificial” groups.

The first type of sacrificial memory is sacrificed (sakrifiziellen), or heroic. It is memory about the heroes who consciously risked themselves or sacrificed themselves for the community.

The sacrificed memory either concerns victories (less traumatic and calmer), or defeats (intense and revanchist, requiring a new war and victory).

Sacrificed memory is militaristic in nature, especially one that seeks revenge.

Sacrificed memory can exist for centuries, eventually transforming into a ritual memory of the group about its “origins” and becoming part of the foundation for collective identity.

The second type of sacrificial memory is victimized (viktimologischen) memory, or mournful, tragic, and is the memory of powerless victims of violence.

Victimized memory is traumatic and painful; it exists only among the generations who have suffered and who remember suffering (“a living memory of three generations”). Following this, even if the executioner pleaded guilty and repented, but didn’t completely disappear historically, the victimized memory is only partially satisfied and at the same time is transformed into a sacrificed, aggressive expansionist format. This results in a “memory of the suffering of ancestors as a feat” and essentially becomes a part of the current politics.

Victimized memory is much less harmless then it may seem at first sight. It demands not just an ‘honouring of the victims,’ and not even simple revenge as a way of victory, but it rather the punishing of the ‘executioner.’ This is not in the form of his ‘penance,’ but in the way of his ‘historic execution,’ more precisely —political dismantling.

At the same time, victimized memory is certainly justified and socially beneficial, but only as a tool of struggle against historical successors of those structures, which have their own skeletons in the closet: criminal states, criminal organizations, criminal ideologies and so on. After the dismantling of these structures, such a memory should be reformatted and become part of the cultural memory and should leave commemorative practices.

That is why it is useless, as political scientist David Riff does, in particular, to urge nations and communities to “forget” their injuries and insults in the name of peace and tranquillity, in the name of not striving for revenge and compensation, and therefore for new conflicts. If the injury is not overcome (if the structure- executioner is not destroyed and continues to exist in one form or another as its historical continuation), the pain from the injury is not forgotten. Pain lasts, often over the centuries, it continues to exist in the form of the most aggressive revanchist sacrificed memory, continues to erode the group’s self-consciousness: just as the ashes of Claes continued to beat upon the heart of Thyl Ulenspiegel.

It is just as futile to try and extend the life of a victimized memory by more than three generations of living witnesses to the tragedy, as well as their relatives and friends. In this case, the victimized memory inevitably turns into its opposite – in the variant of the sacrificed pride, which immediately becomes a tool of Realpolitik. And Germany’s “exemplary repentance” for the Holocaust transforms into the “main” and, to a large extent, the mentoring role of Germany in the structure of the European Union. And the politically institutionalized grief of Israel in connection with the death of 6 million Jews during World War II turns into the demand from the international community not only memorial, but also political preferences for the Jewish state in the Middle East.

Basically, all states whose history contains crimes against humanity and still exist today, should become a thing of the past and dismantle themselves. Only then the trauma of individuals and entire societies will be overcome, even if this trauma is very old. Otherwise victimized memory always will appear through ‘democratic make-up,’ again and again showing up in the form of an instrument of political struggle against the existing order. (I’ll spare you from specific references to concrete dead ends from the history of “countries of the golden billion,” especially when they are clearly visible.) The further the crime recedes in history, the more perverted and farther from the true ideals of repentance and reconciliation this memorial war will be.

I suppose, by this very reason, until countries rich with “collections of skeletons in the closet” like Great Britain, Spain, Germany, USA, France, China etc. are dismantled, the problem of their “right historical memory” will not be resolved and overcome. In my opinion these countries with their “memories” filled with world wars, colonialism, mass terrors, ethnic cleansing and other unforgettable outrages will have to become a thing of the past. And Russia – as a champion in terms of terror against its own people – I think it will be called upon to lead this procession of great powers into historical nonexistence.

So this memory is not just “fun for humanities scholars,” it’s very active and paradoxical, a double-edged chemical weapon, which not only consolidates, but at the same time eats away at a country and society – if this memory turns out to be too saturated with misery, thirst for revenge, hate or shame. This memory as “ash that incessantly beats upon the hearth” should be left behind. This should be done not by simply forgetting, but rather in a way of dismantling the culprits of the crimes, of which we are doomed to remember.

To start with, it should be liberation from the historic power of executioners and their systematic heirs, and only then memorial reassurance.

Daniel Kotsyubinsky